A Firefighter’s Tears

By:

Kenda

*There’s little

I can say about the tragedies that occurred on September 11th, 2001,

that hasn’t been said far more eloquently by so many others. I was profoundly saddened when I watched an

episode of Oprah this week that centered on children’s fears and questions

as a result of the terrorist attack on our nation. Quite frankly, I was surprised at how much children between the

ages of six and ten understand about this tragedy, and in turn, how much it’s

affected them. These were neither

children who had lost a parent or family member on that day, nor children from

New York or Washington D.C. Instead,

these were kids from the Midwest whose fears encompassed the same things my

fears encompass and your fears encompass.

Possibly I recall my own childhood through rose colored glasses, or

possibly the way we are now given instant news reports twenty-four hours a day

on three-hundred channels has changed how much children are privy to. I don’t

recall having the insight to various events from my youth in anywhere near the

way the children of this new century have insight into what occurred on

September 11th. It touched

me in ways I can’t describe when a ten-year-old girl said she cried because of

all the children who lost a parent, or both parents, in that Tuesday’s

attack. Then there was the girl, no

more than eleven, who said she’s unable to sleep because of the haunting images

she saw on TV. And the weeping nine

year old boy who is so devastated by the death toll he can’t stop his tears.

And finally, the two young sons of a flight attendant who are begging their

mother to quit her job. That made me

consider how the children of firefighters must be feeling right now. And, as a writer, that inspired me to bring

to life, once again, a little boy who has appeared in two previous stories of

mine, and whose papa is the fire chief of a fictional town known as Eagle

Harbor, Alaska.

Chapter 1

It was a

day when many parents across the United States picked their children up from

school. It didn’t matter if you lived

in New York City or Washington D.C., where the tragedies occurred, or if you

lived in a small hamlet in Alaska known as Eagle Harbor. As a parent you felt a strong need to be

with your child. To make sure your

child was safe. To rejoice in your

child’s innocence and well being, while at the same time embracing him in a

long, firm hug he didn’t understand the reason for.

“You’re

squeezing me too tight, Papa,” Trevor Gage had told his father when Johnny

picked him up from school the afternoon of Tuesday, September 11th,

2001. “And don’t hug me in front of the other guys. I’m too old for this kinda stuff.”

Trevor was

nine now and in the fourth grade. It hadn’t been very long ago that he wasn’t

too old for a public hug from his father, but of course, he was correct. He

was nine. No longer five, or six, or

seven, but nine. Not a little boy

anymore, but a few years away yet from being a young man. On the brink of that difficult passage that

would leave childhood forever behind while his adult years loomed ahead, still

a clean slate and filled with so much promise.

John Gage

had been on a twenty-four shift at Eagle Harbor’s fire station when a phone

call from the police chief, Carl Mjtko, awoke him at five-fifteen that morning.

Carl was calling from his home a few blocks from the fire and police

station. He quickly relayed what little

information he knew about the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center.

Though the likelihood of

such an attack happening in Eagle Harbor was so remote Johnny couldn’t even

begin to quote the odds, the fire and police departments were put on full

alert. Johnny pulled his bunker pants on, slipped his feet into his boots, and

walked to the dayroom. The only other

firefighter pulling that twenty-four hour shift with him did the same. Johnny turned the TV on then poured himself

a glass of milk. Like Americans all

across the country, he watched the video replays in disbelief as Peter Jennings

narrated the action. Not that you

needed a narrator. In this case the

pictures were worth a thousand words.

A thousand words, and a thousand tears.

An odd thought, John

supposed, but one that immediately came to mind. So many tears would be shed today, and in days to come. Of that fact Johnny had no doubt.

All

those people. So many, many innocent

people just lost their lives because of these senseless acts.

Johnny

had barely finished his milk before a third plane smashed into the

Pentagon. It was then, as other

firefighters and police personnel began to arrive, that he realized he didn’t

look much like a leader standing there in his bunker pants and T-shirt with his

hair still mussed from sleep. It was

difficult to leave the vicinity of the television set, but Johnny headed down

the corridor for the locker room. In

fifteen minutes he had showered, shaved, brushed his teeth, and was dressed in

the khaki slacks and red shirt that indicated he was Eagle Harbor’s Fire and

Paramedic Chief. He returned to the

kitchen just as Peter Jennings reported a plane suspected to have been hijacked

as well, had gone down in an open field outside of Pittsburgh.

John

Gage’s workday normally ended at eight a.m. after pulling a twenty-four hour

shift. That meant he had time to go home, pick up Trevor, and drop him off at

Eagle Harbor Elementary School prior to the start of classes at eight-thirty.

Because of the alert Johnny stayed on duty that Tuesday morning. He called his home shortly before eight and

talked to the woman who served as housekeeper, nanny, surrogate mother, and

friend. Clarice Mjtko was the police

chief’s mother and had been a resident of Eagle Harbor for all her sixty-eight

years. The one and only time she’d left

Alaska was in July of 2000, when she’d flown to Los Angeles with Carl to bring

Johnny and Trevor home after John’s frightening ordeal with a crazed man from

his past.

“Oh, John,

the news,” Clarice had said softly into the phone. “I can’t believe it. It

doesn’t seem real. Those poor people.

It’s so sad. All I want to do is

cry, but I can’t. I don’t want Trevor

to see me.”

“I doubt

anyone can believe it right now, Clarice. And I imagine a lot of people will be

crying over the next few days.” Johnny

shifted the subject a bit then. “Listen, I won’t be able to come home this

morning because we’re on full alert.”

“Yes, I’m

aware of that. Carl called me.”

“So you’ll

take Trevor to school for me?”

“You know

I will.”

“Does he

realize what’s going on?”

“No. He’s had his breakfast and has been out to

the barn to feed the animals. He’s

upstairs now brushing his teeth and combing his hair. Or at least that’s what he’s supposed to be doing. Knowing that

boy of yours he’s likely gotten sidetracked.”

Johnny chuckled. “It’s a strong possibility. Especially when his ultimate destination is

school.”

“I need to go check on him

in a minute.”

“Take the phone to him,

please. I’d like to talk to him.”

“All right.”

“Oh, and, Clarice?”

“Yes?”

“Don’t say anything to

Trevor about these hijackings. I want.

. .well, he’s only nine. I’d like him

to remain a little boy as along as possible.

There’s no point in him worrying about things no kid should have to deal

with. Especially since events like that

are highly unlikely to happen in Eagle Harbor.”

“I understand. And no, I won’t say anything to him. I was

watching the news on the TV in my room before Trevor got up and then while he

was in the barn, but I haven’t turned the living room TV on, and I’ve left the

kitchen radio off.”

“Thanks, Clarice. I don’t know what I’d do without you.”

If Clarice had a nickel

for every time John Gage had expressed that sentiment to her since he’d moved

to Eagle Harbor with his infant son in 1993 she’d be rich. But then, just being a part of Trevor’s life

had been reward enough. Carl was

Clarice’s only child and had never married.

To Clarice, Trevor was the grandchild she’d never had.

Johnny talked to his son

briefly that morning. The only

explanation he gave Trevor as to why Clarice would be taking him to school was,

“I’ve got some things to do here at the station, Trev. I’ll try to pick you up after school. If I can’t, Clarice will bring you by so we

can have supper together.”

“But you’re supposed to go

off-duty at eight, Papa. How come

you’ll still be working when I get out of school?”

“I might still be

working. But I might not be either. One way or another I’ll see you after

school, okay?”

Trevor thought his

father’s answer seemed rather vague, but he responded with an, “Okay. Love you, Pops!” before handing the portable phone back to Clarice.

“Love you too, Trev,”

Johnny said softly as he hung up the phone in his office. He wondered how many

other fathers and sons had gone through this same scenario hours earlier in New

York. Fathers who wouldn’t be coming

home to their little boys tonight, or any other night ever again.

With a heavy heart John

Gage returned to the kitchen. Like most Americans on that September 11th, he

spent the day watching the horrifying and sorrowful events play out on television.

When the south Trade tower collapsed it was Johnny who made a prediction long

before Peter Jennings did. To the

people assembled around him John said in a hoarse voice, “We’ve just lost so

many.”

“So many what,

Chief?” A young man asked.

“So many fellow

firefighters. That building had to be filled with them. They would have been evacuating people. Firefighters and police officers both.”

Johnny remained in the

dayroom long enough to watch the north tower collapse, then to hear Mayor Giuliani

report three hundred firefighters were missing in that mass of rubble. He retreated to his office shortly

thereafter and sat down at his desk. It

was so easy to imagine being where those men were now. There had been a time in

his life, a long time, when John Gage had worked for big city fire

departments. First in Los Angeles,

later in Denver. If things had worked

out differently between Johnny and Ashton, Trevor’s mother, he might have been

employed by the New York City Fire Department right now, rather than residing

in the small town of Eagle Harbor. He

might have been one of the three hundred missing or dead. That was a thought

John Gage, as the single father of a nine-year-old boy, didn’t want to dwell on.

At least Ashton’s safe.

Though Johnny’s

relationship with the cardiac surgeon had ended years ago, she was Trevor’s

mother. The boy only saw Ashton two weeks out of each year, but Trevor loved

her nonetheless. Johnny knew Ashton and

her husband were currently in London conducting a symposium for leading cardiac

surgeons from around the world. Ashton lived and worked in New York City. Johnny was glad he didn’t have to be

concerned about her whereabouts, or be concerned with whether or not she was

safe.

One less thing to deal with on this day of all days. Where my former

lover is. Where the woman I wanted to marry is.

Those were thoughts best left in the past. That was

aided when the phone rang. The caller

didn’t have to identify himself. The fire chief knew immediately who it was

when the man spoke just one word.

“Johnny?”

John gave a soft smile. “Hey, Roy.”

“Are you okay?”

That question told John Gage two things. Roy had been following the news with the

same attention he had, and Roy had just seen the reports on the missing

firemen.

“What a day, huh, Pally?”

Johnny could detect a tiny smile in Roy’s voice at

his use of the old nickname.

“Yeah, Junior, what a day.”

“Thirty years ago that woulda’ been us, Roy.”

“What do you mean?”

“Going in those buildings. Evacuating people. Storming up flights of stairs to reach the

people trapped above us. We would have

done it because we were trained to.

Because it was our job. Who the hell woulda’ thought those buildings

would come down like that? And so fast.

They never had a chance, Roy.

The rescue workers never had a chance to get out.”

“No, they didn’t,” was all Roy said because Johnny

spoke the truth. Those men and women,

firefighters and police officers and harbor patrol agents, didn’t have a chance

to get out. And yes, thirty years ago it could have been him and Johnny. They had worked together in the second

largest city in the United States.

They’d done rescues in skyscrapers on several occasions. What made this

massive rescue effort gone wrong so tragic was that it didn’t have to

happen. It was a deliberate act

instigated by a man whose name Roy couldn’t pronounce, and whom the authorities

couldn’t locate with any great certainty.

John Gage and Roy DeSoto talked a long time that

morning. The connection they shared

through years of working together as firefighters and paramedics brought each

of them comfort on a day when the only comfort to be had came from small

things. Small things like talking to an

old friend or hugging your child.

Pleasures Johnny, like most people, often took for granted until

something of this magnitude happens and you realize how lucky you are, and how

it’s the small things that make life worth living.

At twenty minutes after

three, John left the fire station to pick up Trevor. His squinted as he stepped

into the afternoon sunshine. The fire chief hadn’t even noticed the sun was out

that day. It didn’t seem right that the

sky was so blue and bright on a day when Heaven’s angels were surely crying.

Chapter 2

It was

after Johnny had embarrassed his son by hugging him in the schoolyard that the

fire chief led the boy to the red Dodge Durango. Eagle Harbor’s assistant fire chief, Phillip Marceau, was

remaining at the station while Johnny went home. If John were needed he’d be called back. Otherwise, Phil had encouraged him to pick

up Trevor along with instructions to enjoy the remainder of his day off.

Trevor sat

in the passenger seat and dug a sealed envelope out of his backpack.

“Here. This is from Mrs. Harper. I’m supposed to

give it to you.”

Johnny raised a

questioning eyebrow. Trevor was a lively boy, but he didn’t cause problems in

school. Johnny had never been given a

sealed note before.

“Did you get in trouble

today?”

“Nope. I was a model

child, as always.”

Johnny looked away so his

precocious son wouldn’t see his smile.

“Then what’s this about?”

Trevor shrugged. “I dunno.”

While Trevor secured his

seatbelt Johnny opened the envelope and pulled out a form letter. From his parking

spot in the school’s lot he silently read it.

Dear Parents;

By now you are aware of the tragic events that rocked our

nation early this morning. The staff of Eagle Harbor Elementary School

concluded the children in grades K through 5 are too young to be overwhelmed by

the constant flow of information and horrific images being broadcast on

television. Therefore, today’s events

were not discussed with children in those grades. As a parent, it is for you to decide how much of this tragedy you

wish to discuss with your child. If

your child asks questions about the events we encourage you to answer those

questions in a way your child can understand.

Please remember, above all else, it’s important at a time like this to

assure children they are safe and will be protected by the adults entrusted

with their care. As always, the staff

of Eagle Harbor Elementary School is here to assist you. Please do not hesitate

to speak to your child’s teacher if you need guidance before broaching this

subject in your household.

Sincerely,

The Eagle Harbor

Elementary School Staff

Johnny folded the

letter. He put it in a pocket of the

khaki jacket he was wearing that had the fire department’s logo on the front

and his rank insignia on both sleeves. As they drove through the quiet, rustic streets of Eagle Harbor

Johnny didn’t mention the letter he’d just read. Instead, he asked Trevor about his day in school.

“School

was okay. I got an A on my math test.”

“Good for

you. Do you have a lot of homework?”

“Some.”

“Then

after chores and supper you need to get started on it.”

“I knew

that’s what you were gonna say. You say

it every single time when you pick me up from school. I’ve been goin’ to school

since I was five, Papa. By now I have

the routine down pretty good, okay?”

Johnny

laughed. “Okay.”

“Besides,

I got another problem, Pops. A big

problem.”

“And

what’s that?”

“You know

that girl I like? Brooke?”

“I’ve

heard you mention her a time or two, yes.”

“Well, I gotta

figure out a way to dump her.”

“Dump

her?”

“Yeah.

See, it’s like this.” Trevor turned in

his seat as much as his lap belt would allow so he was facing his father. “She’s an older woman. In the fifth grade. Now I thought this older woman thing would

be good for me. You know, help me

settle down a little. Make me more mature. Stuff like that.”

“I see.”

“For a

while I guess it worked. For a while. .

.about two whole days, I actually kinda enjoyed feeling like I was in the fifth

grade. But you know what, Pops?”

“What?”

“Pretending

to be ten ain’t all it’s cracked up to be.

Brooke. . .she doesn’t want me to play with the guys anymore. She wants me to play with her at recess and

only her. And she gets mad if I talk to

any other girls.” Trevor laid a hand on

his chest. “Now personally, I think

there’s a lot of fish in the sea and I’m not ready to reel one in yet. I think Brooke has the wrong idea.”

“The wrong

idea how?”

“She keeps

using words like ‘commitment’ and ‘going steady.’ Papa, I don’t wanna go steady with any girl. I don’t care how cute she is. I’m just a kid. I gotta lot of good years left in me. I wanna have some fun before I settle down and start a family.”

It was all

Johnny could do to keep from laughing.

After what he’d witnessed on television nothing could bring him more

pleasure than this inane conversation with his son.

“Well, it

sounds to me like you do have a real problem there, Trev.”

“No

kidding. So what should I do?”

“First of all,

don’t hurt Brooke’s feelings.”

“No. I

don’t wanna do that. I just wanna know

how to dump her. When we visited Uncle

Roy this summer Mr. Kelly told me you know all about dumping women. Or did he

say you know about women dumping you?

Whatever. Anyway, maybe you

could give me some pointers, huh?”

“The next

time we visit Uncle Roy I’m going to make certain Mr. Kelly isn’t invited

over,” Johnny mumbled.

“What’d

you say, Papa?”

“Never

mind. Okay, Trev, here’s what you

do. Tell Brooke that you’d like to be

her friend, but that right now your father says you’re too young to have a

girlfriend.”

“Wow! That’s a great idea, Pops! It makes you look like the bad guy, and I

end up smelling like a rose.”

“That’s

right. It makes me look like the bad guy, which doesn’t matter considering I’m

far too old to ever be concerned with asking Brooke for a date, and you end up

smelling like a rose.”

“She’s in

the fifth grade, you know.”

“Pardon?”

“Brooke. You said you’re too old to ask her for a

date, but she’s in the fifth grade.”

“I realize that. But I’m still too old to ask her for a

date.”

“I guess,

but she is pretty mature.”

“Not

mature enough for me by a long shot.”

“Okay. If you say so.”

Father and

son rode in silence for a mile before Trevor spoke again.

“Papa, why did those bad

men steal planes today and crash them into buildings?”

Johnny

glanced at his nine year old. “You know

about that?”

“I heard

some of the big kids talking on the playground. They got to watch it on TV in

their classrooms. So how come the bad

men did that?”

“There’s

not an easy answer for that, Trev.

First of all, I doubt if those men were ever taught right from wrong by

their parents.”

Trevor’s

eyes widened with disbelief.

“You mean like they were

never told it’s wrong to steal an airplane and crash it into a building?”

“Exactly.”

“Pops,

you’ve never told me it’s wrong to steal an airplane and crash it into a

building, but even so, I know I’d be in big trouble for doing it.”

Johnny

smiled at his son. “Then you’re a lot

smarter than those hijackers.”

“What’s

that word mean?”

“Hijacker?”

“Yeah.”

“It means

to commandeer a plane or a vehicle of some sort. To steal some means of transportation.”

“Oh. Well

if they needed a plane, how come they just didn’t take it and land it at their

own houses? How come they flew the

planes into buildings?”

“They were

trying to make a statement, Trev.”

“What kind

of statement?”

“By flying

those planes into buildings the hijackers think they can tell us our way of

life here in America is wrong. They

think that by flying those planes into buildings they can tear down our way of

life. What they don’t realize is that

being an American has nothing to do with how tall our buildings stand, or where

our military leaders report for work.

Being an American is about freedom.

It’s about the right to choose, as individuals, what is best for each

one of us. It’s about the right to hold religious services in whatever house of

worship we desire. It’s about the right to vote for the men and women we want

to run our country’s government. And

being an American means coming together as a family when something bad happens. It means coming together to rebuild what was

destroyed, and it means coming together to fight in order to keep our country

safe and free.”

“Like

soldiers do?”

“Just like

soldiers do.”

“If we

have a war will you be drafted?”

Johnny

chuckled again. “No, kiddo, I won’t be

drafted if we have a war. Just like I’m

too old to date Brooke, I’m also too old to be drafted.”

“Will

Uncle Roy be drafted?”

“No. Uncle

Roy’s too old to be drafted as well.”

“What

about Chris or John?”

“Chris’s

disability would keep him from being drafted, and he’s too old for the draft

also, as hard as that is for your papa to believe. As far as John goes, I doubt he’d be drafted, Trev. John provides a valuable service to this

country as a forest ranger. Regardless, I really don’t think you have to worry

about him being drafted. Actually, I

don’t think you need to worry about anyone being drafted. For now the men and

women currently enlisted in our military would be deployed if an act of war is

declared.”

“I heard

the older boys say we’re gonna fight some guy named Ben Landon.”

“His name

is Osama bin Laden. And at this point no one knows for certain if he was behind

these attacks, so it’s too early to predict who we might or might not fight.”

“Papa, were there people on those planes and

in the buildings? People besides the

hijackers I mean. I heard Justin say

so.”

Justin was

Justin Crownwell, a thirteen-year-old grandson of Nana Marie - one of Clarice’s

many sisters.

“Yes, Trev,

there were people in those planes and in the buildings.”

“Were they

hurt?”

Johnny

gave a slow nod. “Some of them were

hurt, son.”

“Did any

of them die?”

The fire

chief didn’t answer his son until he’d driven the Durango down their long driveway

and parked it in front of the garage.

He turned then and looked into Trevor’s dark brown eyes.

“Yes,

Trev. Some of them died.”

“Why would

those bad men want to do that? Why

would they want to kill people just because those people are Americans? What did we ever do to them?”

“Kiddo, I

don’t know.”

“But it’s

not right, Papa. People shouldn’t die

just ‘cause they got on a plane to go visit someone. We got on a plane to go see Uncle Roy and Aunt Joanne this

summer. We shouldn’t have to worry that

a bad person is gonna crash that plane into a building when we’re going on our

vacation.”

“You’re

right, we shouldn’t. And we don’t have

to. This was a very isolated incident,

Trev. The government is already

discussing ways to increase security at airports around the country. We can’t let this make us afraid. If we do, then those bad men win. Then they have a power over us we can’t let

them have. You don’t need to be afraid.

New York is a long way from Eagle Harbor.”

“But Mom

and Franklin live in New York. And

they’re in London right now. They have

to fly home next week. What if bad men get on their plane?”

“Bad men

won’t get on their plane. There will be a lot of security at Heathrow – the

airport in London your mom and Franklin will fly out of. You don’t need to worry about this,

Trevor. Mom and Franklin will be fine.”

“But what

if the bad men come back? What if they go to Los Angeles where Uncle Roy, and

Aunt Joanne, and Jennifer, and Libby, and Chris, and Dixie live?”

“They

won’t.”

“Promise?”

John Gage

sat in the vehicle a moment wondering how you make a promise to your nine year

old that nothing bad will ever happen in the world again, when age and

experience tell you that’s not true.

“Trevor, I

can’t make a promise that bad things won’t happen to people we love. We always hope that’s the case, but

sometimes it’s not. What I will promise

you is that I will always be here for you, and that we’re very, very safe. Eagle Harbor is a very safe place to live.”

“But a bad

man came here and kidnapped you.”

“Yes, a

bad man did. But I’m okay now, aren’t

I?”

“Yeah.”

“And you

know Evan Crammer is dead and that he can’t ever hurt me again, right?”

Trevor

dropped his eyes so his father wouldn’t see the tears the frightening memory of

a man named Evan Crammer brought forth.

“I know, Papa.”

“Okay

then. That’s all that matters.”

Johnny unlatched his

seatbelt then unlatched the belt encircling his son’s slim waist. He pulled the boy to him and gave him a firm

hug while kissing the top of his head.

“You’re safe, Trevor. Papa will always keep you safe. Eagle Harbor

is a great place to live. We don’t have

to worry about hijackers coming here.”

Trevor

nodded against his father’s strong chest.

He wrapped his arms around Johnny’s middle for a long moment before

finally pulling away. He picked his

backpack up from the floor of the vehicle, opened the passenger door, and

climbed out. He paused to look at his papa.

“But what about

the kids in New York?”

“What

about them?”

“You can

tell me we’re safe here in Eagle Harbor, and I believe you because I know Eagle

Harbor is a good town. Everybody is nice here.

No bad men crash planes into buildings.

But what about the kids in New York?

What are their papas gonna tell them tonight when they ask if they’ll be

safe?”

Trevor

didn’t wait for his father to answer him, which was just as well because Johnny

had no answer for his boy. He watched

as his nine year old carried his backpack by the straps and trudged to the

house as though he had the weight of the world on his shoulders.

Johnny

remained in the Durango thinking over Trevor’s question.

But what about the kids in New York? What are their papas gonna tell them tonight

when they ask if they’ll be safe?”

“I don’t know, Trev,” Johnny said

softly as he stepped from the vehicle.

“Papa just doesn’t know.”

_____________________

Johnny shielded his son

from the news on television that night.

Overall, that wasn’t difficult to do since John rarely allowed Trevor to

watch TV on a school night. Between

chores, supper, homework and the need to take a shower, there was rarely time

left for TV before Trevor was sent to bed.

If time was to be had, Johnny had long ago gotten into the habit of

playing a board game with his son or reading to him. The subject of the

terrorist attacks wasn’t brought up again that night by either Trevor or

Johnny.

John’s day off was

Wednesday. He took Trevor to and from

school. Once again Trevor didn’t

mention anything more about Tuesday’s tragedy so Johnny didn’t either. And once again, the television was kept off

in the Gage household after Trevor returned from school in the afternoon. It wasn’t until the boy had gone to bed, and

Johnny knew he was asleep, that the fire chief settled into his recliner and

turned on the big screen TV in the living room. He kept the volume low so it wouldn’t wake Trevor up. Johnny watched as firefighters worked

through the night searching for survivors.

He could imagine the despair they were feeling by now, but trying so

hard not to show. He was proud when he

saw the replay of the three young firemen raising the American flag over the

rubble. He got a lump in his throat

when he heard about one firefighter who had taken a vacation day Tuesday. That vacation day spared the man’s life. All

twelve of his shift mates had died when the first tower collapsed. Johnny knew the sorrow felt by that man, who

was now helping with the rescue efforts, had to be overwhelming. Johnny thought about his days at Station 51

and the camaraderie he’d shared with Hank Stanley, Mike Stoker, Marco Lopez,

Chet Kelly, and of course, Roy DeSoto.

To be called in from vacation to report to the scene of a disaster only

to discover those men you worked with, and by and large lived with, were

dead? It was heartbreaking to even

consider it, let alone realize a man was living through that experience right

now. A man who was thankful he’d be

able to go home to his wife and children when this was all over, while at the

same time a man wondering why he was still alive and his friends were not.

On Thursday Clarice

brought Trevor to the fire station after school, as was their habit when Johnny

was on duty. Johnny was in meeting with

the members of the police and fire commission, and Clarice was soon involved in

conversation with Carl’s secretary, leaving Trevor to his own devices. That didn’t matter to the boy. Eagle Harbor’s fire station was Trevor’s

second home. He’d been just a year old

when they’d moved here. He didn’t remember his father working anywhere else.

The three young

firefighters seated around the television turned to look when Trevor entered

the room.

“Hey, little chief,” came

the greetings.

“Hi, guys.”

Trevor helped himself to

three cookies from the cookie jar, and then poured a glass of milk from the

quart container his father always kept in the refrigerator. He sat at the table eating his after school

snack. He had an unobstructed view of

the television in the dayroom area of the big kitchen. He laughed when Crazy Kenny turned to look

at him and pretended to be picking his nose and eating boogers. Crazy Kenny did lots of weird stuff that

made Trevor laugh. Of course, some of that same stuff made Papa frown and say,

“Ken, knock it off.”

Trevor’s smile faded when

the television cameras zoomed in on the destruction in New York. This was the

first time he’d seen the damage the planes had done. Trevor’s mother and stepfather had an apartment in Manhattan

across from Central Park so he’d been there a number of times. He’d even eaten

in a restaurant called Windows on the World.

Windows on the World was on the one hundred and seventh floor of the

World Trade Center, almost at the very top.

But that restaurant wasn’t there anymore because Peter Jennings said the

giant pile of rubble Trevor was seeing used to be the Twin Towers of the Trade

Center.

Trevor felt like Peter

Jennings was looking right at him when he said, “And it is estimated that close

to three hundred firefighters are still missing after being caught inside the

Twin Towers when they collapsed. Though firefighters and other rescue workers

haven’t given up hope at finding the men alive, with each hour that passes hope

grows a little dimmer.”

Before Peter Jennings had

a chance to say anything else, and before Trevor had a chance to see his

father, the klaxons went off. Crazy Kenny hit the off button on the remote

control, tossed the instrument on a shelf then ran from the room. After the fire trucks had pulled out of the

station, and Johnny had pulled out of the lot in the Fire Chief’s Durango,

Clarice took Trevor home.

Clarice noticed the boy

was subdued when he came in from the barn after feeding the animals. She asked Trevor what was wrong, but only

received a quiet, “Nothing,” in return.

At six-thirty Clarice went to the stairs and called for Trevor to come

to supper. The boy emerged from his bedroom.

“But Papa isn’t home

yet. He was supposed to get off work at

six.”

“Maybe he’s still on that

call they got while we were at the station.

Come on, love, it’s getting late. You know Papa always says not to wait

for him if it reaches six-thirty and he’s not home yet.”

“But I wanna wait.”

“No. No waiting. Supper is hot. It’s time to eat.”

Trevor was unusually quiet

throughout the meal. He kept turning in his chair to look out the bay window

that gave him a clear view of the front yard and driveway.

“Trevor, turn around and

eat please.”

“Where’s Papa?”

“Love, he’ll be here soon

I’m sure. He’s either on a call or he’s

finishing up things at the station. Now

eat so you can start your homework.”

“Do you think something

bad happened, Clarice?”

“Like what?”

“Do you think a building

might have fallen on Papa?”

Clarice knew Johnny hadn’t

allowed Trevor to watch any television the last few days, and she wasn’t aware

of what the boy had seen at the fire station.

Therefore, she smiled at what she perceived to be Trevor’s silliness.

“No, Trevor, a building

hasn’t fallen on your papa. Eagle

Harbor doesn’t have any big buildings to begin with, and in the sixty-eight

years I’ve lived here I’ve never seen any of the buildings fall down. I’ve seen a few men fall down coming out of

the Golden Nugget Saloon, but I’ve never seen any buildings fall.”

“It could happen though,

Clarice. Sometimes bad things happen

that no one thinks is possible.”

“Sometimes they do, but

not very often in Eagle Harbor, love. Now eat your supper.”

Clarice stood to clear her

empty plate. Trevor contemplated what

she’d just said. He thought she was

wrong. They had an airport in Eagle

Harbor. Gus Zimmerman owned it. Bad men

could take a plane from that airport and crash it into the Eagle Harbor Medical

Clinic. The clinic was three stories

high. It was the tallest building on

Eagle Harbor. Maybe that’s what had

happened. Maybe bad men stole one of

Gus’s planes and crashed it into the clinic, only Clarice didn’t want to tell

Trevor that. Maybe Papa was in the clinic right now helping people get

out. Just like those firefighters in

New York were helping people to get out when the Twin Towers fell.

“Clarice, I think maybe

bad men took a plane and—“

Before Trevor could finish

the phone rang. He listened to the

one-sided conversation and quickly discerned it was Nana Josephine, one of

Clarice’s sisters. Trevor knew that

meant this conversation could last a long time.

Clarice didn’t notice the

boy scrape most of his food into the garbage can before putting his empty plate

in the dishwasher. Trevor retreated to

the living room where he stared out the massive picture window until it grew

too dark to see. When he disappeared

upstairs Clarice thought Trevor was doing his homework. But homework was the last concern Trevor had

that night. With the images from the television still vivid in his mind, along

with Peter Jennings saying, “And it is estimated that close to three hundred

firefighters are still missing after being caught inside the Twin Towers when

they collapsed. Though firefighters and other rescue workers haven’t given up

hope at finding the men alive, with each hour that passes hope grows a little

dimmer,” Trevor retreated to his father’s room. He curled up on the big bed, clinging to Johnny’s pillows while

he cried.

Chapter 3

Johnny arrived home

shortly before eight that evening. When

he asked Clarice where Trevor was she said, “Upstairs doing his homework. Your supper is in the oven, John.”

“Thanks. Sorry I’m late.”

“That’s okay.” The woman bustled around the kitchen,

grabbing her purse, jacket, and a manila folder. She had an eight o’clock meeting at the Methodist Church. Because of her job for the town’s fire

chief, Clarice sometimes missed events she had planned to attend due to a call

he was on, or some other occurrence that held John up at the station. But since John was home now, Clarice could

leave.

“Tell Trevor I said

good-bye.”

“I will.”

Johnny smiled as he

watched the woman hurry from the house with her purse under one arm and a

folder of church materials under another.

He was glad he’d gotten home in time for Clarice to make her

meeting. God knew she’d missed enough

meetings over the years because of his schedule.

The fire chief hung up his

jacket in the laundry room closet then bent to unlace and remove his

boots. He placed the boots on the

closet floor then opened the door that led into the vast, homey kitchen. He walked through the kitchen and into the

great room. He climbed the stairs to

the upper floor calling, “Trev!” as he went.

Johnny paused when he came

to the landing. Trevor’s bedroom was

dark, as was the bathroom. The hallway

light was off as well; meaning Trevor’s study nook was dark.

He can’t very well be doing homework in the dark. And he never goes to bed before eight-thirty

on a school night unless he’s sick.

“Trevor?”

Johnny questioned as he flipped his son’s light on. The room was empty, the bed still neatly

made.

Johnny flipped on the hall light. Panic hadn’t started to set in yet. Like a

typical boy, his nine year old sometimes liked to hide and jump out at him with

a loud, “Boo!”

“Trev?

Trevor, where are you?”

Johnny paused a moment to listen. It was then that he heard what sounded like

muffled sobs.

“Trev?”

The man followed the sobs to his bedroom. He turned on a bedside lamp just as Trevor

was sitting up. The boy swiped an arm

across his eyes as his father sat down beside him.

“Trev, what’s wrong?”

“Noth. . .nothing.”

“It doesn’t look like nothing.” Johnny reached out and used his thumbs to

wipe the remaining tears from Trevor’s face.

He brushed the boy’s bangs away from his eyes then plucked a Kleenex

from the box on the nightstand.

“Here. Use

this to wipe your nose.”

Trevor did as his father instructed, then leaned over

to toss the tissue in a small garbage can.

“Now do you wanna tell me what’s wrong?”

“I guess. . .” Trevor dropped his eyes to the

bed. His wet lashes gleamed in the dim

light. “I guess I got kinda scared.”

“Scared of what?”

“I. . .it’s stupid, Papa. Never mind.”

“It’s not stupid if it’s scaring you so much it makes

you cry.”

“I shouldn’t cry.

I’m nine now, you know.”

“I know. But

just because you’re nine doesn’t mean you can’t cry if something scares you.”

Trevor thought about Johnny’s statement a moment then

looked at his father.

“Papa, Evan Crammer scared you, didn’t he?”

“He sure did.”

“Did he ever scare you so much that you cried?”

Johnny slowly nodded. This wasn’t something he’d ever

confessed to anyone, but for whatever reason it seemed important to do so

now. For whatever reason Trevor needed

to know that yes, grown men do cry.

“I cried the first time I encountered Evan Crammer

many years ago when Jennifer was a little girl. There came a moment when I thought I wouldn’t be able to protect

Jennifer from him because of my injuries, and that frightened me.”

“Did crying help you not feel afraid anymore?”

“No, I guess it didn’t.”

“How did it make you feel?”

“At the time, pretty hollow inside. Very alone.”

“That’s how I feel, Papa. Hollow. Like there’s nothing inside me anymore.”

Johnny took his pillows out from beneath the quilted

bedspread and propped them against the headboard. He reclined against the

pillows then pulled Trevor to his chest.

He wrapped his arms around the boy.

“Why do you feel hollow, kiddo?”

“I saw on the news that three hundred firefighters

are trapped in those buildings, Papa.

In the World Trade Center. You

didn’t tell me it was the World Trade Center those planes flew into.”

“No, I didn’t.

I’m sorry. I didn’t think you

needed to know that right now.”

“Papa, I woulda noticed they were gone the next time

I was in New York to see Mom.”

Johnny smiled. “Yes, I guess you would have.”

“How come the firefighters didn’t get out before the

buildings fell down?”

“Because they were helping people. They were on the upper floors trying to get

people evacuated. They didn’t have time

to get out, son.”

Trevor nodded against his father’s chest. He turned

on his side and hugged Johnny.

“Papa, I don’t want you to be a firefighter anymore.”

“No?”

“Uh huh.”

“Well then, how am I going to earn money so we can

pay our bills, and buy groceries, and so someday you can go to college?”

“I’ve been thinking about that. You could open a pizza parlor and a candy

store, Pops.”

“A pizza parlor and a candy store? Now why would I want to do that?”

“Because everyone loves pizza and candy. It’s sure to make a lot of money, don’t you

think?”

“Not unless all my customers plan on eating Tombstone

Pizza.”

Trevor had to admit that was the one small part of

his plan he hadn’t figured out yet. His

father wasn’t a very good cook, so homemade pizza like you get in a real pizza

parlor was probably out of the question.

“Maybe Aunt Joanne could come live with us and be the

cook. She makes good food.”

“She does,” Johnny agreed. “But I have a feeling your

Uncle Roy would object to Aunt Joanne coming to live with us and leaving him

behind in L.A.”

“He can come, too.

He could. . .Uncle Roy could stock the shelves with candy.”

Johnny laughed.

“I’ll have to throw that offer out to your Uncle Roy just to see what he

says.”

“You don’t think he’ll go for it, huh?”

“I rather doubt it. Your Uncle Roy is happy being the

paramedic instructor for the fire department. I don’t think he’ll want to move

to Eagle Harbor.”

“Could a building fall on Uncle Roy?”

“No, Trevor, a building can’t fall on Uncle Roy. Uncle Roy doesn’t go out on calls. He’s a teacher now. He hasn’t been on active

duty for more than five years.”

“But. . .but,”

Trevor sniffled as his tears started again. “But you’re on active

duty. A building. . .a building could

fall on you, Papa.”

“No it can’t, Trev.”

“Yes it can.”

Trevor started crying harder as he buried his face in his father’s

chest. “It can. I know it can. All

those firefighters. . .they’re all dead, Papa.

I know they are. Their kids. .

.their kids are waiting for them to come home, only they won’t. They’ll never come home again, Papa. Never.”

Johnny hugged his son tightly. He didn’t shush the boy, nor did Johnny tell

him to stop crying. Instead he encouraged Trevor to let out his fears and his

grief. The fears and grief an entire nation was feeling this week, and like a

nine-year-old boy, was having a difficult time putting a voice to.

When Trevor’s sobs began to abate Johnny reached to

his right and plucked another Kleenex from the box. He lifted Trevor’s chin and wiped the boy’s face. He encouraged him to blow his nose, then

threw the Kleenex away.

“Trev, there’s some things I really need you to

understand, and to believe. Can you

listen hard now to what I have to say?”

“O. . .okay.”

Johnny ran a hand through his son’s shaggy hair as he

spoke.

“First of all, the chances of a building collapsing

on me are very slim. We talked about this on Tuesday. Eagle Harbor is a small

town in Alaska, Trevor, not a big city in New York State. Terrorists target areas where a lot of

people are gathered so they can do the most amount of destruction, and where

they know instant TV coverage is a given. Do you know how long it would take

Peter Jennings to get to Eagle Harbor?”

“A while I guess.”

“Exactly. No terrorist

would be interested in this town. But that doesn’t mean you have to be afraid

the next time you visit your mom. The FBI and other law enforcement officers

are working very hard right now to bring anyone involved with the terrorists to

justice. And, our government is working

hard to come up with ways to make everyone safer, regardless of where a person

lives.”

“But the clinic has three stories, Papa. It could

fall on you.”

“And just how would that happen?”

“A terrorist could hijack one of Gus’s planes and fly

it into the clinic.”

“Trev, trust me.

That’s not going to happen.”

“But it could.”

“Anything can happen, son, but the odds of a

terrorist hijacking one of Gus’s planes and flying it anywhere, let alone into

the clinic, is slim to none.”

“Sometimes buildings fall ‘cause of a fire. Or ‘cause they’re not built as good as they

should be.”

“Sometimes they do,” Johnny agreed. “But again, I don’t believe that will happen

to any buildings here in Eagle Harbor.”

“Some of the buildings are really old, Papa. One

hundred years old, Clarice says. Maybe they’re not safe and you don’t know it.”

“I do fire inspections of those buildings on a

regular basis. I feel confident they’re

safe.”

Trevor glanced up from where his head still rested

against Johnny’s chest. “You’re

sure?”

“I’m sure.”

“But what if there’s a fire?”

“Then it’s my job to assist with putting it out.”

“But what if you’re in a building that’s on fire and

it collapses?”

“Then we’ve come to the next thing I need to tell

you, and that you need to understand.”

“What?”

“Trevor, I’m a very lucky man because I love what I

do for a living. Not every man can say

that. Some men work forty years at a

job they hate just to earn a paycheck.

I’ve worked thirty-three years at a job I enjoy and am good at. If I die fighting a fire you always have to

remember two things.”

“What two things?”

“That I died doing a job I loved. That I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished,

and how far I’ve come, since the first day I started working at Station 8 back

in L.A. when I was just twenty-one years old.

I know that might be hard for you to understand right now, but someday,

when you’re a grown man, it will make sense to you.”

“Is that why you want me to go to college? So I can pick out a job I’ll love to do?”

“That’s exactly why I want you to go to college.”

“But what if I want to be a firefighter and paramedic

just like you, Papa?”

“Then I’ll support that choice after you’ve

attended college and earned a degree.”

Trevor nodded.

They’d had this discussion several times in the past year. Trevor was well aware college attendance was

something his papa expected of him.

“You said you had two things to tell me, Papa. What’s

the other one?”

“That I love you more than I can voice, and that even

after my body is no longer here, my spirit will always remain with you.”

“But I thought a person’s spirit went to Heaven after

he dies.”

“It does. But

I think a person’s spirit also lives on inside the hearts of the people he

loves. Does that make sense?”

“I think so.

It’s like when I think of Pacachu. I remember sitting on his lap and

hearing his stories, and that makes me smile.”

Johnny nodded at the reference to his

grandfather. The man had died when

Trevor was five, but the boy had some memories of him and spoke of him on

occasion.

“It’s just like that, Trev.”

“But I don’t want you to die, Papa.”

“And I don’t plan on doing so anytime soon. But it’s important that you understand all

the firefighters who lost their lives in New York on Tuesday were, above all

else, doing their jobs, Trevor. They couldn’t turn back because they were

afraid, or because they had children at home waiting for them. They might have

wanted to turn back, but people needed to be rescued and the firefighters

wanted to help those people worse than they wanted to protect themselves.

That’s what a firefighter does. That’s

the kind of man he is.”

“Have you cried for the firefighters, Papa?”

“Yes, Trevor, I have. I’ve cried deep inside my heart many times for them since

Tuesday.”

“I’ve cried,

too, Papa. I cried tonight until my

stomach hurt ‘cause I was scared for you, and for the firefighters in New York,

and for all the kids whose papas will never come home again. It makes me so sad.”

“I know it does, son.” Johnny kissed his boy’s forehead while saying softly, “I know it

does. It makes me sad, too.”

“So sad that you cry in your heart like you said?”

“Yes. So sad that I cry in my heart.”

“Is that where a firefighter keeps his tears, Papa?”

“Pardon?”

Trevor laid his hand on the left side of Johnny’s

chest. “Here, Papa. Is this where a firefighter keeps his tears so

no one sees them running down his face?”

Johnny gave a slow, thoughtful nod.

“Yes, Trev. At times like these, that’s where a

firefighter keeps his tears.”

Trevor snuggled deeper into Johnny’s chest. He

remained safe and warm in his father’s embrace long after he fell asleep. Johnny knew he should carry the boy to his

own bed, but then he thought of all the children who would never know the

warmth and security of a father’s hug again. It made him hold onto his boy

tighter, and made him thank God for this simple moment that meant more than any

words could describe.

Chapter 4

On Friday the students of Eagle Harbor Elementary

School gathered around the flagpole on the playground to observe a minute of

silence. It was, as President Bush had

declared, a national day of prayer and remembrance.

Trevor already had his head bowed and his eyes closed

when he felt someone take his hand. He

looked up to see his father standing next to him. Other firefighters and police

officers had walked over to the school from the station with John Gage. They stood amongst the children now, their

presence letting the kids know how much their support and prayers meant to

every man and woman wearing a uniform. Regardless of whether that uniform

signified service to a small community like Eagle Harbor, service to a big

state like Alaska, or service to a vast military organization like the Marine

Corps.

The stars and stripes, and the flag of Alaska, both

flew at half mast from the school yard pole, just like flags across the nation

were flying at half mast. As a light wind filled with a nip of autumn gently

billowed the flags from their perch, the principal asked the students to bow

their heads and observe a minute of silence in honor of all the men, women, and

children who had lost their lives as a result of Tuesday’s tragedies. Johnny squeezed Trevor’s hand as together

they bowed their heads and closed their eyes.

When that minute of silent prayer and reflection had passed, the seventh

and eighth grade choir led everyone in singing God Bless America. Johnny saw a lot of teachers wipe their

eyes, and spotted a good number of his employees crying as well. Carl had turned away and was looking toward

the road, but Johnny had no doubt as to why.

The big bear-like police chief, and veteran of the Vietnam War, didn’t

want anyone to see his tears.

When the singing came to an end Trevor released his

father’s hand. Johnny watched as his

son stepped through the crowd and went to stand by his teacher. Mrs. Harper had carried a small wooden box

outside, like the kind a child might stand on in order to make himself seen

over a podium. Trevor climbed on the

box without hesitation, as though something had been prearranged between himself

and the woman.

Mrs. Harper looked out at the crowd as she spoke.

“We didn’t expect anyone to gather with us today

other than faculty and students, but we’re honored that so many of you who

serve our town so bravely have joined us.

This week has been a difficult one for all of us, and most especially

for the children who are trying so hard to understand why innocent people lost

their lives in senseless acts of violence even we grownups can’t explain. I’ve wiped a lot of tears from the faces of

my students, while trying to offer words of reassurance.

“This morning I decided it was time to put away

books, and rulers, and assignment sheets, to instead have my class of fourth

graders express how they’ve been feeling in whatever form they desired. Some of

my students drew pictures of images they’ve seen on television. Two of my students are in the process of

creating a Website that will pay tribute to those who died. Some of my students wrote poems, while

others are working together to compose a song about that sad day. Trevor Gage wrote a letter this

morning. It moved me so much that I

asked Trevor if he’d be willing to share his letter at our gathering here

around the flagpole. As most of you who

know Trevor are aware, one can hardly call him shy, and public speaking is not

a cause for concern on his part.”

The adults in the crowd chuckled, and Johnny felt

Carl jostle him with an elbow as if to say, “Like father, like son.”

“Despite that,” Mrs. Harper said when everyone had

quieted again, “I know reading this letter won’t be easy for Trevor. It’s never easy to share your work with the

public when that work comes from your heart.”

Mrs. Harper smiled at her young student while handing

him the paper he’d given her just an hour earlier.

“Trevor.

Whenever you’re ready.”

Trevor looked from his sheet of white paper to his

father, then back to his paper again.

He’d never considered that Mrs. Harper might be impressed with what he

wrote. After all, a few words on a piece of paper didn’t display talent in the

same way designing a Website did. Nor

was it impressive in the way painting the American flag on a classroom wall was

like Rebecca LaForge had done. Trevor wasn’t sure anyone would even like what he

wrote. Maybe they’d even boo him and

throw tomatoes at him like he’d seen happen on TV shows. But then Trevor looked

at his father again. He saw Papa’s smile, and the ‘thumbs up’ sign that was a

special thing just between the two of them, and was Papa’s way of saying, “Everything’s okay. I’m right here if you

need me.”

The wind ruffled Trevor’s hair as he stood on the

makeshift stage wearing his denim jacket with a red, white, and blue ribbon

pinned to the front. The art teacher

had made the ribbons and passed them out when the students were exiting the

building for the noon ceremony.

Trevor felt Mrs. Harper briefly place an encouraging

hand on his back, and heard her quiet, “Go ahead, Trevor. You can start now.”

Trevor took a deep internal breath and willed his

knees to stop shaking. In a voice

stronger than he thought he possessed, he started to read.

“Dear God;

“My papa

told me bad men hijacked planes and flew them into buildings on Tuesday. I

don’t understand why you let the bad men do this. Couldn’t you stop them? Or were they so bad they wouldn’t even listen

to you?

“Papa said

those men were trying to make a statement.

They don’t like the good things we have here in America like pizza, and

Nintendo, and M&M’s, and lots of TV channels. They want to take those good things away from us. But Papa says being an American has nothing

to do with how tall our buildings are, or where our military people go to

work. Being an American is about

freedom. It’s about the right to choose

what is best for each one of us. It’s about the right to go to whatever church

we want to, or the right to not go to church at all. Being an American is about

coming together as a family to rebuild what was destroyed, and it means coming

together to fight in order to keep our country safe and free. Because of what the hijackers did, America

is a close family again. I don’t think

the hijackers expected that, God.

“I was very

sad when I heard people in those planes died and people in the buildings died,

too. I didn’t know the buildings the

planes hit in New York were the World Trade Center until I saw it on the TV

news. Papa never told me. I’ve been in

the World Trade Center with my mom and Franklin. Franklin bought me lunch there once in a restaurant called Window

on the World that was on the one hundred and seventh floor. Franklin didn’t even mind when I threw my

cheeseburger up on his shoes ‘cause heights make me dizzy. I didn’t know heights made me dizzy until I

was looking all the way down, down, down to the ground. That’s when I barfed on

Franklin.

“I heard Peter

Jennings say three hundred firefighters are missing because the buildings fell

on top of them. That really scared me,

God, because my papa is a firefighter, too.

He has been for years and years. He’s kinda old now, but he can still

run fast and haul hoses. That’s important stuff to be able to do when you’re a

firefighter. Papa was late getting home

on Thursday night and I cried because I thought maybe a building had fallen on

him, too. Buildings in Eagle Harbor, where I live, aren’t very tall, but still,

I don’t want one to fall on Papa. Papa

said he doesn’t think that will ever happen, but I’m still worried. Please don’t let a building fall on Papa,

God.

“Papa is sad,

too, because so many firefighters died. He doesn’t know any of them like he

knows Uncle Roy and Crazy Kenny, but it still makes him feel bad that those

firefighters are dead. Are they with

you in Heaven, God? I hope so. They were good men and women. I didn’t know them either, but I’m sure they

were.

“I asked Papa if he’d cried for the missing

firefighters. He said he cried deep in his heart. Papa says that’s where a

firefighter keeps his tears so no one sees them running down his face. That

doesn’t mean Papa thinks a man shouldn’t cry, God. It just means he knows firefighters have to be brave for everyone

else. You have a big job to do just like the firefighters, God. Do you keep

your tears in your heart, too? If you

do, then I bet this week your heart is so full it wants to burst. That’s how

all our hearts have felt since Tuesday. Heavy, and full, and ready to break

from the tears we cry inside.

“Even though Papa says a building will never fall on

him, and terrorists will never come to Eagle Harbor and hijack one of Gus’s

planes, I still worry about it. Please watch out for Papa and all the

firefighters here in Eagle Harbor. Even Crazy Kenny who Papa says is half nuts,

and the other half insane. Crying in

your heart hurts just as much as crying real tears. I know, because I’ve done

both this week. Please don’t make us cry

anymore, God. America has cried enough,

and it’s hard for me to think of where a firefighter always has to keep his

tears. Sometimes firefighters just need

to be able to cry like the rest of us.

“Sincerely, Trevor Gage.”

John Gage’s tears weren’t kept in his heart that

afternoon, nor did he turn away to hide them from anyone who might be watching.

He allowed them to run unhindered down his face as he knelt to hug his son.

“How come you’re crying, Papa?” Trevor asked when he stood back from his

father’s embrace.

“Because a firefighter shouldn’t always hide his

tears, Trev. Because sometimes people

should see a firefighter cry for the brothers he’s lost.”

Trevor nodded his understanding. He hoped God was

listening when he’d read his letter.

And he hoped God was watching now as the firefighters who were gathered

around the flagpole cried silent tears for the colleagues in New York they’d

never met, but for whom they now mourned.

It was Trevor who took his father by the hand this

time in order to offer strength.

Together they walked into Eagle Harbor Elementary School, the American

flag behind them flying forlornly at half-mast, but waiting. Always waiting until she was fully raised

once again, as she most certainly would be, to fly proudly over the country she

loved.

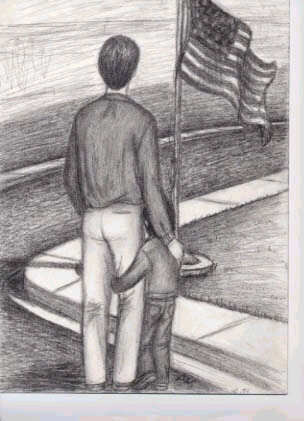

Papa,

Trevor, and the Flag.

*Sketch of Papa, Trevor, and the

Flag by Ria. Please click on Ria’s name if you’d like to send her feedback

regarding her beautiful sketch.

*Trevor Gage appears in two other

stories in Kenda’s Emergency! Library. Dancing With The Devil and The Phantom And The

Parselmouth.